Shu-mi Huang

The Oriental Flower

By Jean Comeau

I don’t believe in talent.

I’ve always said that in life we can obtain anything we wish; we only have to pursue that one dream and not wish for things that obstruct our main desire. But, to be frank, I must admit that I don’t always have the courage and determination to follow this golden rule. That’s why I must sometimes be content with half victories, lukewarm results and half-measures. But nevertheless I remain convinced that great artists, Olympic champions mainly owe their success to their stubbornness, to their unwavering faith in their capacity to reach their goals. “Talent” is a creation of the mind to bring us an easy excuse for giving up. It is more convenient to think that we were deprived of the divine blessing than to admit that we prefer the comfort of failure to the torments of victory.

To continue reinforcing my certainties, I recently met an exceptional mandolinist who owes her success mainly to her courage and her unerring willingness. I met her at the Festival of Mandolin Chamber Music in Bellows Falls, Vermont.

It’s an event where musicians, during four days of intensive work, prepare a concert presented on the last day. The event is organized by the American mandolinist August Watters . Musicians from all over the United States, but also from Canada and, this year, France and Taiwan share their passion for their favorite instrument.

Picture credits: Mathieu Laca

That’s where I met Shu-Mi Huang.

All along, everybody couldn’t stop staring at the exceptional musician that she was; at the final concert, she brilliantly showed her virtuosity by interpreting Vincent Beer-Demander’s Le Tombeau à Calace.

When she began studying music, Shu-Mi took flute lessons at the Tainan University of Technology. Meanwhile, she joined the ChiMei Mandolin Orchestra where she discovered the mandolin. After three years, she decided to carry on with her music studies in France. Although she didn’t really have the financial means, she managed to be admitted in a French school to complete her training. One day, seeing a mandolin hanging on the wall at her professor’s house, she mentioned that she liked to play that instrument in Taiwan. That professor then talked to her about the great mandolinist Florentino Calvo. He even gave her Calvo’s phone number.

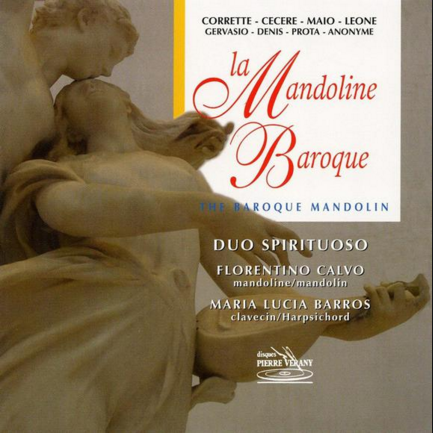

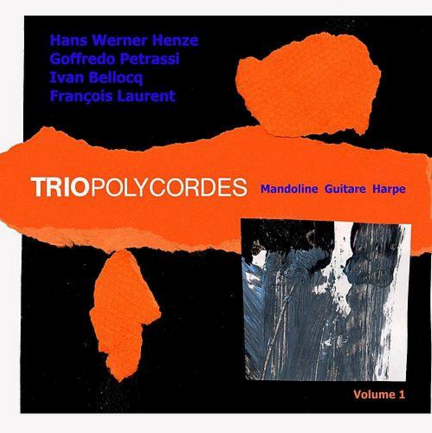

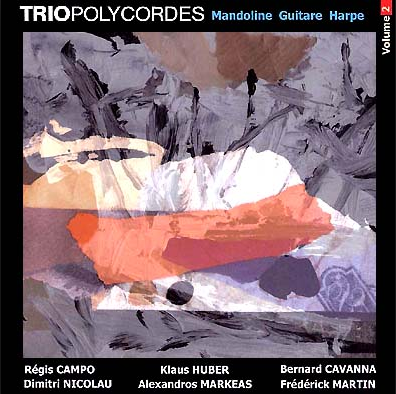

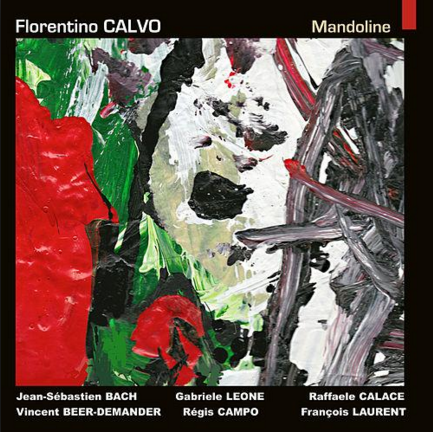

Florentino Calvo is, without any doubt, a major figure in the mandolin world. He teaches the mandolin class at the Conservatoire à Rayonnement Départemental d’Argenteuil. He’s also a famous soloist. He played with several renowned orchestras and recorded great disks. Many of those recordings feature challenging contemporary works in which he shows his brilliant technique. He conducts the MG21 plectrum ensemble .

Let’s say he’s the kind of professor every mandolinist dreams of having.

But Shu-Mi did more than dream: she decided that she would contact the master. She phoned him every day, for six months, sometimes two of three times a day, leaving unanswered messages, before he finally surrendered to her will and talked to her. After she told him how much she really wanted to learn, Calvo agreed to give her a first lesson.

This is when Shu-Mi started to live a real fairy tale. First of all, let’s remember that Shu-Mi didn’t have the money to pay for these lessons; she had the will but not the cash! Impressed by the tenacity of his Taiwanese pupil, the maestro accepted to give her free lessons. After six months of hard work, Shu-Mi was able to prepare her admission at the Conservatoire à Rayonnement Départemental d’Argenteuil. She studied there for six years and became the extraordinary mandolinist that we can now hear.

After her studies, she went back to Taiwan with, in her pocket, the “Diplôme d’Études complet de Mandoline” and the “Diplôme de Perfectionnement de Mandoline” from the institution also known at that time as the Conservatoire de Musique, Danse et Théâtre d’Argenteuil.

While she stayed in France, Florentino Calvo gave her the opportunity to perform as many times as possible in concert, often in solo, to help her develop her self-confidence which was not — should we say — great when she began her studies at the Conservatoire. He also gave her the opportunity to join the MG21 plectrum ensemble and to play with amazing musicians like the mandolinist and composer Vincent Beer-Demander.

During the four days I spent with Shu-Mi, I was literally fascinated. During the first rehearsals, I understood that she was quite a musician. But it’s an unexpected incident that showed me how great she was. At the end of a rehearsal we had free time and I was working on a score that was giving me a headaches. Shu-Mi was practicing in a small living room nearby. Then, the group’s guitarist, Celeste McClain, came in, and asked Shu-Mi if she wanted to play duets, “just for fun”. She suggested the Bolero op. 26 from Calace. “Just for fun?” I tought. I happened to have the score with me. Shu-Mi gave the score a fleeting look and started to play in a performance that would be perfectly acceptable in concert. Then, the guitarist suggested the Mazurka op. 141, also from Calace. Nobody had the score. So we looked on the Internet. Shu-Mi played the piece almost to perfection while I scrolled the score with two fingers on my laptop. It was such a lovely “private concert”!

Shu-Mi has a real passion for the mandolin and for music in general. And this passion, she’s very much able to pass it on. In the weeks prior to the Festival in Bellows Falls, she showed August Watters the score of a piece from the Taiwanese tradition Hoe Na Li Ki.

Since she was very familiar with it, it seamed normal that she would conduct the rehearsals.

She did a tremendous job, even if she had to cope with the fact that the musicians were all speaking English or French while her mother tongue is Mandarin Taiwanese! With a few words, sometimes two in English, one in French and another one probably in Mandarin, she could communicate the atmospheres, the dynamics, the balance between the instruments, and so on.

She was literarily living the music in front of us.

At certain moments during the rehearsals, she played two bars from the first mandolins, then two from de seconds, and, a little later, some from the mandola score, all of it with ease and such passion, just to make sure everyone was feeling comfortable with the part he had to play. Every time someone did something remarkable, she showed her appreciation and never missed mentioning every effort we made with an irresistible smile.

Of course, the final result was remarkable as we can see here in the wonderful video made on the festival by the visual artist, Mathieu Laca.

Meeting Shu-Mi, we often have the feeling that she’s a little girl, cheerful, a bit childish; on the other hand, sometimes she seems so serious, even worried. She is remarkably generous; she always has something to give and is always so eager to please. With the complicity of her precious ally, her sister Mona, she always has a little gift for you or, if not a gift, at least a precious advice, a brilliant trick to play more easily, more brilliantly something you would not even dream of playing. At the end, the great musician always takes over because this is what she is deep down inside.

The world of classical music is a pitiless one. It’s a world restricted to those who have the courage, the willpower of carving their own place after endless hours of relentless work. Shu-Mi belongs to this elite. She will go far; all of those who go alongside her cannot doubt it.

Above all, the world of classical music can’t take the risk of not giving such an amazing artist the place she deserves under the sun. Who among the Aonzo, Avital, Lichtenberg, Acquavella or Reuven will give her a little boost now?